Yu Juncong—the author of the first open letter to Jasic Technology and one of the first Jasic workers to openly protest the company’s policies—was fired in May 2018 for his actions. On July 27, he attempted to re-enter the factory along with other fired workers who had raised their voices against the company and, along with his wife and younger brother who were there in support, was arrested. Yu is one of the four workers being officially tried in the Jasic incident.

The following is Yu’s story, based on his wife Huang Lanfeng’s recollections.

“To not let anyone be picked on, that’s what I call ability”

Yu was born in 1993 in the mountains of Shangrao, Jiangxi, in a village where the telephone lines were only put up in the last few years. The oldest of the family’s children, he chose to drop out of the vocational middle school he had tested into in order to help the family make ends meet. A lot of people say Yu is smart and it’s a shame he didn’t finish school, but he doesn’t mind the comments. When friends or relatives tell him he ought to have some ambition, he laughs. “What do you mean ambition? To become a petty office worker? You’d be yelled at the boss and have your wages withheld all the same. To not let yourself be picked on, to not let anyone be picked on, that’s what I call ability.”

Yu was smart, but he never used it to step on anyone’s head, or try to climb the ladder. Instead he learned what he did to try to make life better for himself and those around him.

Always One to Stand against Injustice

Yu was always one to stand up against injustice. His fight at Jasic Technology was not his first head-on battle with wealthy, powerful urban elites. His first experience in fighting collectively for his rights and those of other migrant workers around him was not in a factory, but in an urban village, another fixture of migrant worker life.

At the time, Yu and his wife Huang lived on the second floor of an urban village building, the kind of hastily erected building thrown up by local villager-landlords to make money off migrant workers flocking to China’s manufacturing hub Shenzhen. One night at around 2 a.m., unable to sleep because of the heat, Yu and Huang heard calls of “fire!” Unable to escape, they, along with another semi-conscious man Yu dragged out of the hallway, barricaded themselves in their room and covered their noses and mouths with wet towels, waiting for help to come. Only the three of them and a few others in the building survived the fire; a dozen-plus died. Meanwhile, almost all the hard-earned possessions of the buildings’ residents were lost in the fire. The fire had been caused by substandard electrical wiring and other inadequate safety precautions.

While Yu and Huang were still in the hospital recovering from smoke inhalation, they and the other tenants received news that the village committee was only going to compensate them 200 yuan (about $30) for damages. Though still supposed to be confined to his hospital bed, Yu immediately began to rally others to confront the village committee. After over a week of negotiations, the tenants won a month’s rent in compensation, money that although insufficient compared to the damage done, was critical for many tenants to find a new home after the fire.

At the time, Yu was only 20.

Yu had always been an avid learner. He filled his notebooks with jottings on labor law—knowledge that no doubt gave him the confidence to call out Jasic Technology’s wrong-doings. Another favorite of his was the Chinese version of “The Internationale,” the song he led others in singing during the Jasic protests. Two lines of the song’s lyrics are underlined in his notebooks: “Who is it who created this earth? It was us the working masses. All things belongs to us the workers, idle parasites we won’t tolerate.” [Editor’s note: These lines are from the Chinese version.] Both his knowledge and his sense of justice made him a pain in the eyes of Jasic management.

The Struggle at Jasic

Yu arrived at Jasic in January 2017. Although Jasic had a reputation for being better than a lot of other factories in the area, Yu soon discovered all kinds of unfair treatment and bullying of workers at the factory and took to raising his voice against them.

By July 2017, Yu had met several others who shared his dissatisfaction with the factory’s scheduling practices. Along with ten other workers, he went to the Labor Bureau offices to complain about the factory’s illegal adjustment of work schedules and the practice of deducting two days wages for one day off. Though illegal, it’s common for employers to adjust work schedules in ways that prevent workers from enjoying a regular schedule and being able to plan their free time. For example, employers force workers to take weekday breaks so that they can make them work on the weekend. During the busy season, they make workers work continuously over weekends without overtime pay in return for idle time during the low season. Deducting double-pay for days off is also illegal according to Chinese labor law. For leading action against this illegal practice of the company, Yu and another co-worker were denied overtime and assigned cleaning duty as punishment. Workers at Jasic, like most other Chinese factories, rely heavily on overtime to make a living. The minimum wage in Shenzhen is 2,200 yuan ($317) a month without overtime. But workers say they only take home around 1,000 yuan ($145) after deductions, which include the company’s accommodation and meal fees, plus social security and tax deductions.

Despite suffering this reprisal, in March 2018, Yu raised another grievance, this time against the company’s mandatory employee hikes. Jasic management forced workers to participate in 10 kilometer hikes, cutting into their rest. Yu took screenshots of other workers’ criticism of the hikes and shared these in the company’s main Wechat group, openly raising his voice against the mandatory hike practice. For this he was once again punished with denial of overtime. Although Yu was the only one to raise the problem head on, the grievances he expressed were widely felt, and Yu didn’t let the threat of punishment prevent him from stepping forward to protest these daily abuses of power by the company.

The incident which led to Yu’s firing was another protest against abusive company culture. In early May, warehouse department manager Rong Zhengzhi yelled at Yu, who took out his phone to record the incident, unwilling to accept such verbal abuse and intent on collecting evidence of Rong’s behavior. Seeing Yu pull out his phone, Rong began to hit Yu and accuse him of playing with his phone. Yu promptly called the police, and both Rong and Yu were taken to the police station to settle the dispute. Yu later posted an account of the situation on his social media account, and also sent out a call for the firing of such a “crude and hooligan-like manager”.

That night, Yu received a text from HR manager Guo Liqun informing him he was fired for skipping work for three days. Yu had taken two days of annual leave and one day of personal leave, all of which he had submitted leave applications to his manager for, and all of which had been approved. His official notice of dismissal read, “Logistics Management Department delivery worker Yu Juncong, male, employee number 1006051, from joining the factory on January 6, 2017 to April 23, 2018, has cumulatively skipped 3.5 days of work.”

Yu’s regular criticism and protest of the factory’s practices made him the target of management’s ire, and the factory fabricated an excuse to fire him, hoping this would eliminate a thorn in their side. Yet Yu continued to pay attention to the situation of his co-workers at the factory, and when co-workers Mi and Liu were abused and illegally fired two months later, he joined his former co-workers in attempting to re-enter the factory and assert his and his co-workers’ rights.

Yu was arrested in the July 27 factory entry conflict, and is currently in the Shenzhen No. 2 Detention Center, one of the four workers awaiting trial as leaders and instigators of the Jasic struggle. But as he once said, “All we want is a wage raise, and to get back the money that we were unfairly fined. Is that wrong? What’s wrong with that?” Whether Shenzhen’s judges think there’s something wrong with that remains to be seen.

Reposted from Labor Notes: https://labornotes.org/blogs/2018/11/jasic-detainee-3-story-yu-juncong-always-standing-against-injustice

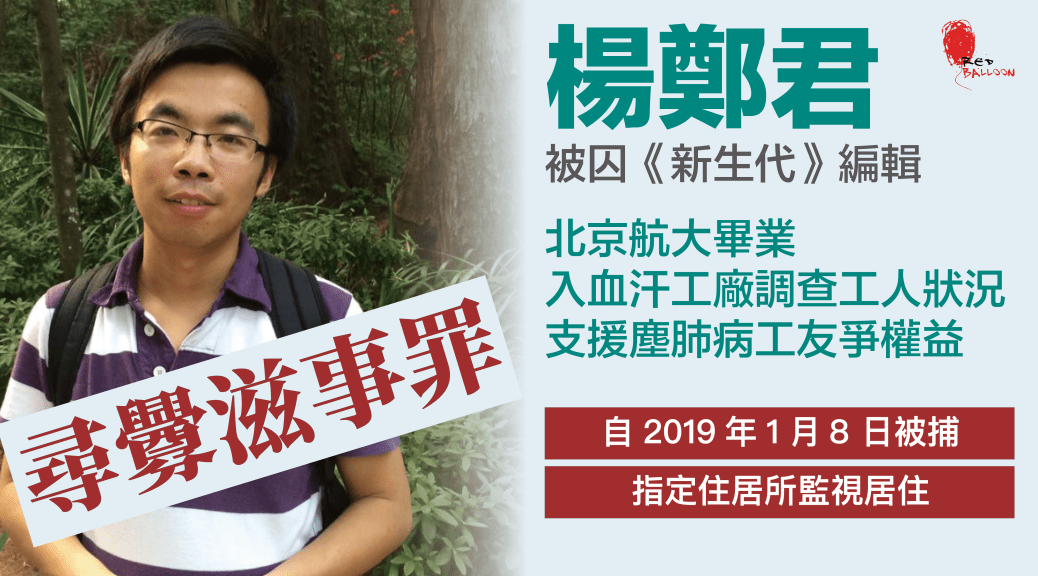

Yang Zhengjun

Yang Zhengjun