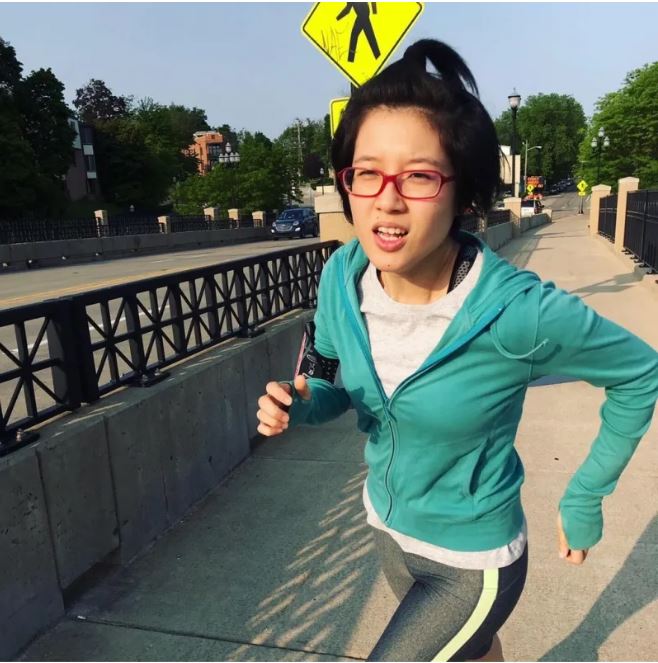

Zheng Churan began to run when she had run out of options to save her husband from the police.

Over the past month she has covered almost 90 miles, running in circles around the city where she lives in southern China. She tracks her progress via Weibo and Twitter every day and plans to keep running until she’s completed 6,200 miles (or 10,000 kilometers), which is the distance between where her husband was arrested in China and the Old Trafford stadium in England, where his favorite soccer team, Manchester United, plays.

Zheng’s husband, Wei Zhili, went missing from their home in Guangzhou more than two months ago, in late March. Zheng told BuzzFeed News his disappearance was a “blow to the heart and head.” But it did not come as a surprise — Wei is a journalist and labor activist, exactly the sort of person who gets in trouble with the police in China. Zheng herself had been picked up by the police on almost exactly the same date four years earlier.

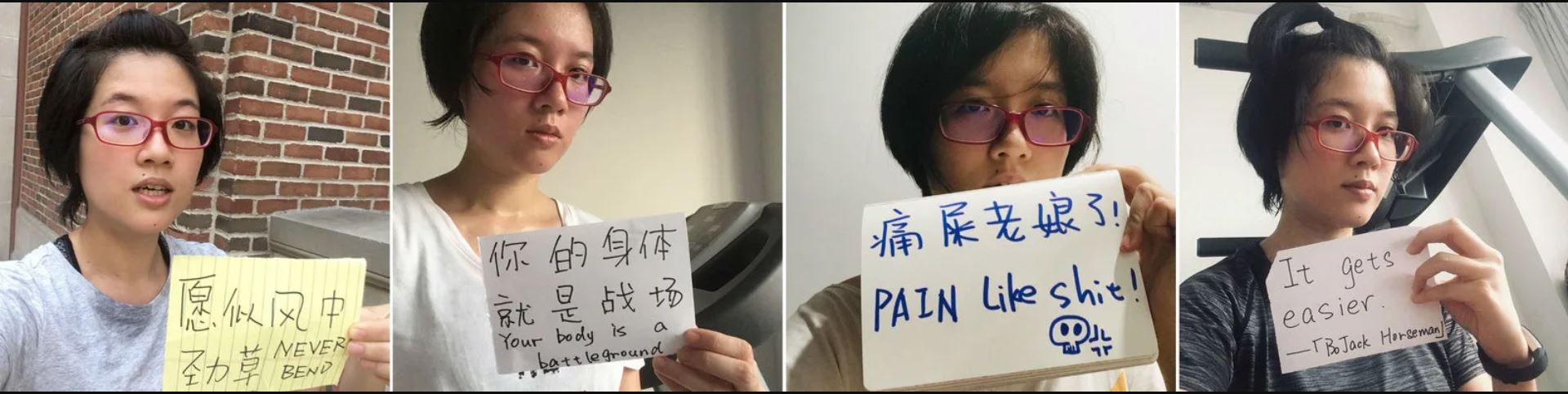

Zheng was one of five women detained by police in 2015 for handing out stickers against the sexual harassment of women on subways and buses. The official charge was for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” a crime punishable by three years in prison. As writer and journalist Leta Hong Fincher notes in her book Betraying Big Brother, the five women — Zheng, Wu Rongrong, Wei Tingting, Wang Man, and Li Maizi — were virtually unknown at the time of their arrest. But the timing of their detention — just before International Women’s Day and as Chinese President Xi Jinping was about to cohost a summit on women’s rights in New York — turned their arrest into an international scandal, making them famous as the “Feminist Five.” Zheng and the four other women were released the following month after 37 days in detention.

Four years later, when her husband disappeared, Zheng knew the authorities were behind it, but that did little to console her. She tried everything to get answers — she visited three public security bureaus and two local police stations; called 12389 (China’s police reporting line), 110 (a general line for police complaints and to report disappearances), and 12345 (a general public administration service line); and wrote a message on Weibo that was shared over 6,000 times.

Zheng, 30, finally heard from the police one week after her husband disappeared. They told her that he had been picked up for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” — just as she had been four years prior. He was being held, for the time being, in a detention center two hours away in the city of Shenzhen. Although the officer on the phone told Zheng that Wei was doing fine, he would not be allowed to see a lawyer or his wife. There was no telling when — or if — Zheng would ever see her partner again.

That was when she began to run. Over email, Zheng told BuzzFeed News that she was running to bring attention to Wei’s incarceration, but also because she had simply “run out of campaigns” and didn’t know what else to do. Zheng shares a daily update on her runs on Weibo and Twitter with the hashtag #RaceToFreeWeiZhili. Twitter is banned in China, and Zheng, like many other young Chinese people, uses a VPN to circumnavigate the ban.

“He is detained under scrutiny, which means we don’t know where he is,” she said. “His lawyer is also unable to meet him — no human rights activists under scrutiny have ever met their lawyers, according to my knowledge.”

Zheng’s political and personal lives were always closely intertwined but became more so when she met Wei at Guangzhou’s Sun Yat-sen University in 2013.

“He would speak to me every day about the living conditions of workers, why sanitation and construction workers had to work so hard, but were still very poor. They are not lazy or stupid, it is that society has structural problems that allow the rich to become richer while the poor become poorer,” Zheng wrote about her husband after he was detained, in an essay in the Hong Kong Free Press — a free, nonprofit online newspaper founded by independent journalists in response to concerns over declining press freedom. “Zhili forced me to think about all these issues that I rarely considered. If he wasn’t my boyfriend, I probably would have kicked him in the face to make him stop talking. But he was so persistent! Eventually, I became a feminist who also focused on workers’ rights.”

Zheng believes Wei’s disappearance is part of a crackdown on labor activists and left-leaning students in China. Wei is the editor of a pro-labor website called New Generation that monitors and reports on migrant workers.

“I always felt that he might be arrested one day because he helps workers, which pisses off the government for disturbing stability,” she told BuzzFeed News via email. “As a feminist, I have experienced a lot of this when I was arrested in 2015, but as the relative of an activist, it feels quite different.”

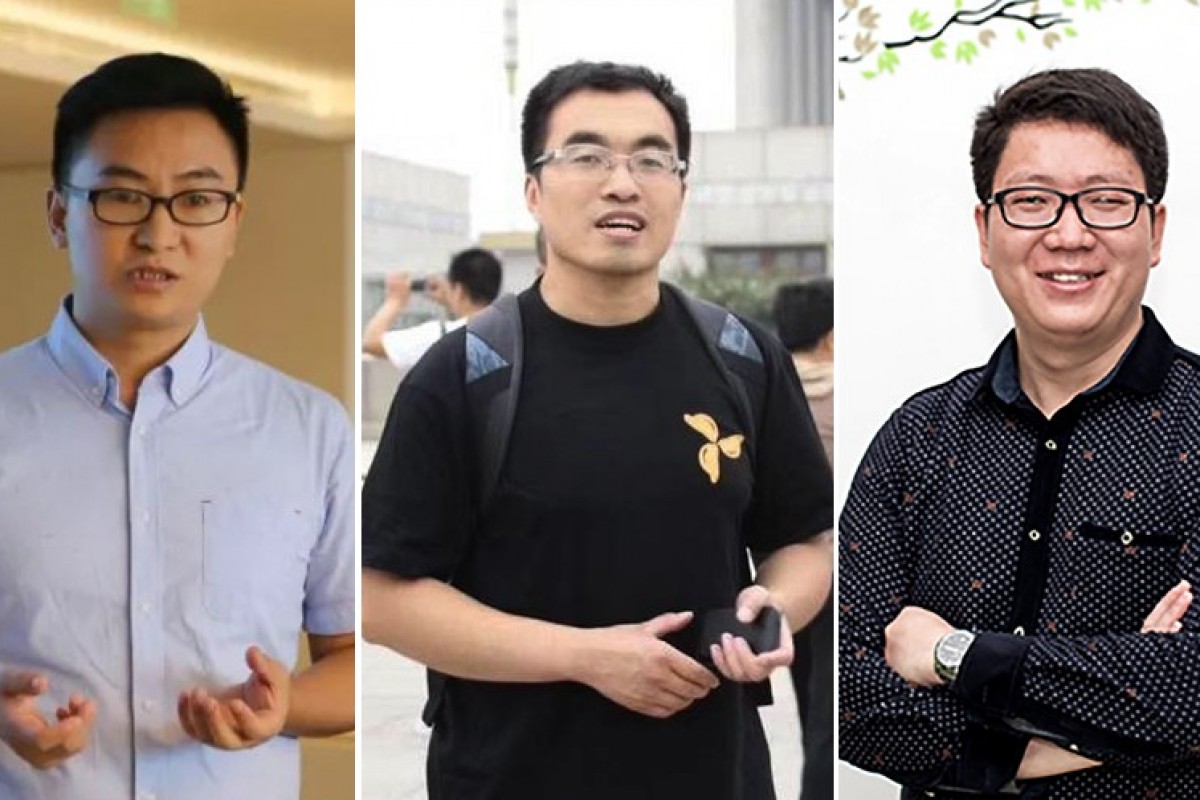

In the months before he was arrested, Wei, who is 31, was helping workers suffering from an incurable lung disease — pneumoconiosis, the most common occupational health hazard in China — to file legal claims against their employers. The day Wei disappeared, two of his coworkers, Yang Zhengjun and Ke Chengbing, were also reported missing.

After Wei disappeared, Zheng literally grew sick with worry. As she comforted Wei’s parents and her own, her anxiety began to manifest in physical symptoms: She coughed up blood, lost her appetite, couldn’t keep food down, could not sleep, and stayed glued to her phone day and night, waiting to hear from Wei.

In the fog of her depression and helplessness, Zheng told BuzzFeed News, she imagined that Wei’s ideal partner would be someone strong and capable of withstanding what she was dealing with, “someone with an eight-pack, who could hold him up with a single hand.” She decided to start running — with the goal of completing 6,200 miles and sharing social media updates about it — as a way to bring awareness to Wei’s incarceration and to fight her way out of the sadness that threatened to engulf her.

A lifetime of feminist campaigns and encounters with the state, Zheng said, meant she had devoted herself to work, spending little time caring for her body.

“Although I’ve been doing a lot of things for him in the past month, I am mentally exhausted. I decided to train myself and run to strengthen my mental power and health, so I can take better care of our parents and greet a free Wei soon.”

Zheng wakes up at 9 every morning, stretches, runs, stretches some more, and does squats and high-intensity interval training.

“My beloved disappeared because he did something good. It breaks my heart,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I am now trying very hard to rebuild my courage and my trust in the world.”

When she first began to run, Zheng said she was surprised: “I felt better. Focusing on my own body actually feels good. But at the same time, when I run I recall the good days with Wei, so I cry and run at the same time.”

Zheng’s 37-day detention in cell number 1107 caused her years of PTSD.

In prison, her glasses were taken away so she could not recognize the faces of her interrogators. Other members of the Feminist Five — particularly those who identified as queer — were sexually harassed by guards and lawyers, and the police frequently used threats against family members to intimidate the women.

Describing her state of mind to Fincher, Zheng used the Chinese term pujie, which translates as “spread out on the street,” like roadkill. At the time, Zheng had no way of knowing what was happening to her family back in Guangzhou, but Wei and his network of supporters in the labor rights community were keeping the authorities at bay with a constant vigil around Zheng’s parents.

Zheng did not recover from the effects of incarceration for a long time after she was freed. Fincher described Zheng’s deep shock, how she would grow afraid whenever she heard a knock at the door, terrified of being arrested again, and remembering the hazy faces of her interrogators and her prison.

Even after her release, Chinese police would keep Zheng in a constant state of anxiety by randomly calling her up for a “chat” or inviting her for “tea.”

After months of therapy, Zheng married Wei in 2016, promising her parents that she would not work for women’s rights until the government dropped all charges against her. The Feminist Five were released when lawyers for the prosecution failed to present evidence and charges against them within the mandated period of 37 days, but they are still considered “suspects” by the police.

Zheng is no longer running alone. Thanks to her followers on Weibo and daily running updates on Twitter, she’s been joined by eight other people who heard about Wei and her through the internet. “Some of them are avid athletes, while some seldom do any sports, but they all support me and Wei with this,” Zheng told BuzzFeed News. “Some pay little attention to social activism or civil society, but after they heard about Wei and my story, they ran over 10 km with me and said that they hoped to share 100 km with me. It was deeply moving and filled me with power.”

Among their followers and friends, Zheng and Wei have always been referred to as “knight errants.” Both of them, Zheng wrote in her essay about Wei, grew up in middle-class families in the 1990s with a culture of heroes and warriors, which taught them: “At the sight of injustice, draw a sword and render help. In other words, we had to help others who are treated unfairly, and speak up for them or else we wouldn’t be able to become our ideal selves.”

Zheng is still afraid, but these days, she said, she’s putting one foot in front of the other.

“I think no one can avoid the fear of leaving family behind, losing freedom, and being imprisoned,” she wrote in the essay. “We turned to words that we had always used to encourage one another: ‘My feet are trembling with fear, but how can I not do it?’”

Reposted from Buzzfeed News: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/nishitajha/zheng-churan-feminist-five-china-running?fbclid=IwAR3eP7cqPNUb2MMHF4GXju5JUaIPAAk5NUDMIanGQkMPDjRXZpTRJGkN0TE

Three more people detained as China continues to crack down on labour groups

Three more people detained as China continues to crack down on labour groups