On May 8, 2019, the offices of Lengquan Hope Community, a non-profit organization serving the children of migrant workers,were ransacked. The leader of the organization, a professional social worker who has for years served migrant workers and who not long ago had set out to visit the villages of pneumoconiosis-afflicted migrant workers, disappeared the same day. He was later confirmed to be in Residential Surveillance in a Designated Location. His wife Zhou Lijuan was apprehended at the Lengquan Community offices the same day, and was subsequently released, but Li Dajun has been missing to this day. The following two articles written by netizens about Li Dajun give an introduction his many years of work with migrant workers, but fail to explain why such an outstanding social worker and non-profit leader was arrested.

More News of Disappearances

洪水之涛 2019.05.08

Article reposted from the Chinese original on Red China: http://redchinacn.net/portal.php?mod=view&aid=39117

I see in my Wechat friend circle someone else has disappeared. The author of this old article, Li Dajun.

The Conditions of Low-level Construction Contractors: the Extreme Result as Murder or Suicide

It is reported that the offices Li Dajun’s Hope Community in Lengquan Village, Xibei Wang Town, Haidian District, Beijing were ransacked this morning. His wife Zhou Lijuan was taken away in front of the family’s elders and their one year old daughter. Their computers, hard drives and other items were also confiscated. Other Hope Community staff were isolated for questioning, including on whether there were foreigners or Taiwanese and Hong Kong people who visited, where Hope Community’s funding came from, and whether there was subversive discourse at Hope Community. Police warned Hope Community staff that they could be held guilty for knowing and not reporting.

Li Dajun was out of the office at the time and is still unreachable, so we cannot confirm whether he has also been arrested. The police did not leave any legal documents when taking away Li Dajun’s wife Zhou Lijuan, so it is not clear whether she is merely being summoned for questioning or whether they are enacting criminal coercive measures. We also do not know which department is handling the case.

The full name of the Lengquan Hope Community (冷泉希望社区) is “Ten Percent Donation Scheme Lengquan Village Youth Hope Community” (十分关爱冷泉村青少年希望社区). It was founded on September 24, 2011, initiated by the China Youth Development Foundation, funded by the Hong Kong Ten Percent Donation Scheme Foundation and the Shih Wing Chin Foundation, supported by Peking University-Hong Kong Polytechnic University Social Work Research Center, and implemented by the Beijing Xingzairenjian Cultural Development Center as a non-profit project to serve the children of migrant workers. It is located in Lengquan Village, Xibei Wang Town, Haidian District, an area in Beijing well known for its concentrated migrant worker population. It was the first comprehensive community service center for the children of migrant workers founded as part of the China Youth Development Foundation’s Hope Project.

As the primary person in charge of the Lengquan Hope Community, 38-year-old professional social worker Li Dajun has lived in this Beijing urban periphery village alongside migrant workers since 2011. Since graduating from university, he has always been committed to social welfare undertakings such as environmental protection, rural re-construction, and migrant worker rights protection. He has served variously as a project officer of the Lashihai project of the Yunnan Provincial Public Watershed Management Research and Promotion Center, a project coorindator of the Peking University-Hong Kong Polytechnic University Social Work Research Center, and the chief coordinator of the Beijing Xingzairenjian Cultural Development Center. He has long been been concerned with and involved in the education and organization of front-line workers. This work includes relief work with pneumoconiosis-afflicted migrant workers. Just a few days ago, he rode over twenty hours by hard-seat train, covering 1,700 kilometers from Beijing to Hunan Sangzhi, to deliver donations to sufffering pneumoconiosis-afflicted workers deep in the mountains.

In 2012, Li Dajun published the Occupational Safety and Occupation Protection in the Construction Center Investigative Report on occupational injury, which was later commented upon by the main leaders of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and facilitated the implementation of the regulations on construction workers’ occupational injury insurance. In 2015, he wrote the research report “A letter from a non-Beijing mother – how many ‘proofs’ does it take to my child enrolled”, which enabled tens of thousands of non-Beijing school-age children who have difficulty entering school to attend school, enabling them at least in primary school to avoid the bitterness of becoming of left-behind children and being separated from their working parents.

Zhou Lijuan is Li Dajun’s like-minded partner. She has always worked with him in his public welfare work and is the mother of two young children.

I hope that Dajun and his wife are safe! I hope even more that these young volunteers who have always cared for the children of migrant workers can return home as soon as possible and care for their own one-year-old and six-year-old children.

Another Advocate of Public Welfare Disappeared: One Week Since Li Dajun Went Missing

Shuang Xi

I still remember the first time I saw Li Dajun.

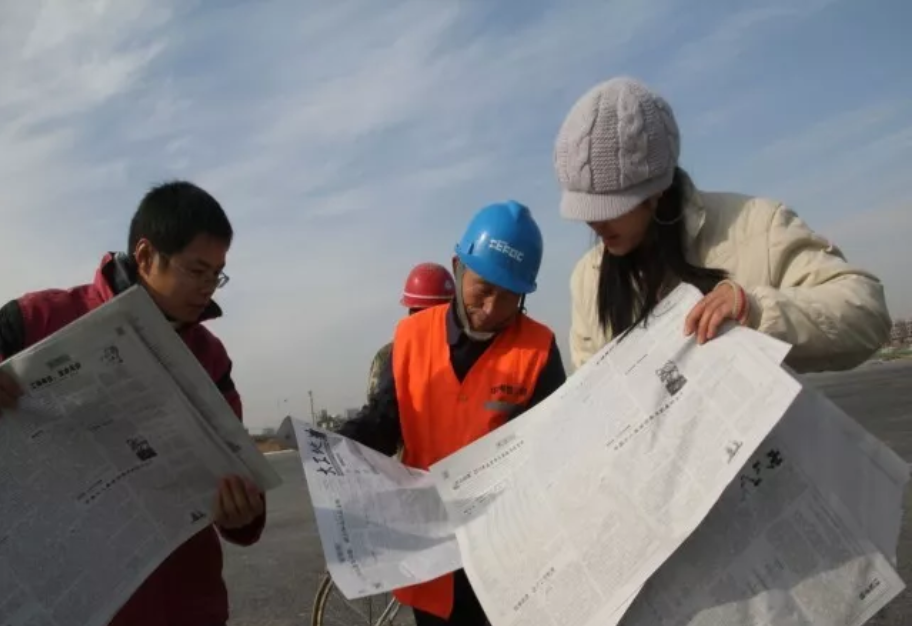

At the time I was still a young student. My friends and I went to a construction site to meet workers and distribute a newspaper called the Da Gongdi [the great construction site]. It was Li Dajun who took us there then. Through the introduction of a friend, I learned that Li Dajun has been engaged in research about workers as well as providing service them and that he was a well known activist in the non-profit world. The stack of Da Gongdi I was holding, was not only the product of many years of toil by Dajun and many other volunteers, it was, more importantly, welcome spiritual nourishment for workers.

After we visited the workers, Dajun gave us a more in-depth introduction to Da Gongdi. In 2009, he and a group of comrades, with the help of enthusiasts coming from all walks of life, established a construction site reading room. But, the reading room was short on reading materials that suited construction workers. Because Dajun and his friends wanted to focus on real needs springing up from workers’ working and living conditions, they started publishing and distributing the Da Gongdi newspaper. Although Da Gongdi was only four pages long, it contained news about society, commentary on current events, information about labor law, and a column where workers could express their own thoughts, among other things. It truly was “small but complete in every way.” At its peak, more than 15,000 printed copies were not enought meet the demand of the readership.

Telling us all this, Dajun suddenly stopped. “Actually,” he laughed, “there’s another very important reason why Da Gongdi is so popular among workers.”

We were all hanging on his words: “What reason? Tell us!”

Seeing how anxious we were to know, Dajun’s grin grew even larger: “Some workers told me that the paper Da Gongdi uses for printing is of much better quality then other newspapers. Because of its combination of brittleness and firmness, it’s perfect when used as toilet paper! Hahaha!”

Upon hearing Dajun’s weird reply and his mischievous laughter (I only later found out he was always like this), I also couldn’t help bursting out laughing. This seemingly serious, unusually down-to-earth activist actually a sense of humor. How could he not make a strong impression on people?

From Rural Yunnan to Construction Sites

Dajun isn’t someone who studied to work with migrant workers in university, but various experiences in his early life planted that seed in him. Perhaps this is that mythical work of ‘fate’ people talk about.

In 2000, when Dajun was still an undergraduate in the Department of Social Work at Yunnan University. He came across an article about women workers in the University library. He learned about the Shenzhen Zhili fire in 1993, and how that fire had claimed the lives of 87 women workers, while another 51 were left with a lifelong disability. The women were all young, their average age less than 18 years old.

Perhaps this article led him to recall his own life in the year of 1993. He was only 12 at that point. His older sister was 18 years old, the same age as the young women working in the Zhili factory when the fire happened. That winter, his father who was a construction worker, had not been paid his wages. Dajun said that Spring Festival that year was the worst he had ever experienced. Also in that year, his sister began to develop respiratory diseases from working in a textile factory, which have continued to this day. The family once thought that this was a common chronic disease. It wasn’t until 2009, when Dajun met Hunanese pneumoconiosis workers in Shenzhen, that things suddenly clicked, and wondered whether his sister also suffered from an occupational disease. “There is such an intersection between the fate of different people,” Dajun wrote in his blog.

Students who graduate from the social work department rarely engage in social work, and even fewer choose to serve in rural areas. However, after graduating, Dajun chose to take up social work in rural Yunnan, and he stayed there for three years. Later, he also spent three months on a construction site in Kunming, moving bricks every day. He has suffered two work-related injuries and met Yi [ethnic minority] youngsters sent to work [on construction sites] by their families to make them kick their drug habits. After work every day, he and his fellow workers would eat barbecue, drink beer, and chat. He said that when he was working on the construction site, he had no special feelings. But every time he would see how difficult life was for migrant workers and workers from the rural areas, he felt that he really wanted to be able to help them.

In 2007, he was still looking for direction. One of his teachers recommended he join the Beijing University Social Work Research Center, to participate in research on construction workers and to understand the employment system of the construction industry.

In order to better understand the living conditions of the workers, Dajun began going for in-depth visits with workers outside of the formal investigation, and witnessed the hardships of the workers’ lives: plain unpeeled boiled potatoes made up their lunch, while the workers’ dormitories were in bad condition with no hot water. In the still cold spring, workers only had access to cold water to eat, drink and wash with. The dormitory only had low-voltage electricity that was insufficient to heat water. “The workers worked but didn’t get paid. Bosses gave the workers homemade food vouchers instead of a salary . To buy food the workers would take these food vouchers to the canteen run by the boss’ wife, and to buy cigarettes or alcohol they would go to a convenience store also run by the boss’ wife. The price of these goods was often double the price on the market.”

During that period, one of the workers named Lao Pan died in the dormitory. This deeply hurt Dajun. Lao Pan’s co-workers later told Dajun the story of what had happened: on the day of the incident, the 57-year-old migrant worker Lao Pan was assigned to a large rock and had to use hammers to smash the rock up. He was told he must be finished in one day, otherwise he would not be paid for that day. “By the afternoon, he said that his heart was hurting a lot, but he insisted on finishing the day’s work. When he came back he was so uncomfortable he didn’t eat and went straight to lie down in bed. Since he had no money to see a doctor, he thought it might get better if he just slept.” Before the incident, Lao Pan had already been working on this high-end real estate site for 35 days in a row, more than 11 intensive hours per day.

“Could Lao Pan, who was in critical condition, use food vouchers to go to a hospital outside the construction site to see a doctor? When he went out to work, he took 200 yuan from home and spent more than 100 yuan on train tickets. When he died, all he had left was one yuan and five mao.” When interviewed by China Youth Daily in 2016, Dajun was filled with anger upon recalling the story of Lao Pan.

Later, Dajun tracked and investigated more than 100 cases of migrant construction workers’ wages arrears and work injury claims. He would stay at construction sites overnight, sleep in the open air, and visit the hometowns of the migrant workers to complete this work. He once stayed up all night on watch with workers in order to catch their boss. He has also had plenty of experience of being kicked back and forth by various agencies and departments, and has also experienced construction sites hiring thugs to take revenge against him. Dajun describes himself as a listener and a companion, and I think that since then he has never had any doubts about what he needs to do. As a result, this is the eleventh year of his time as a “listener” and a “companion.”

Flowers of hope planted in Lengquan

When workers recall the first time they saw Dajun, with his glasses and clean clothes making him “look like someone sent by the boss”, they did not trust him. Later, when Dajun and student volunteers sent clothes, food and money to workers suffering from occupational injury and helped them out during legal proceedings, workers noticed and remembered: “I think Dajun and those folks with him are genuinely concerned, they treat us like brothers, they don’t come here to take advantage of us and that’s why we trust them.”

In 2009, Dajun and his comrades set up and registered the Beijing Xingzai Renjian Cultural Development Center, which primarily serves those migrant workers whose “labour rights are most difficult to ensure, whose living conditions are most arduous and whose cultural life is most lacking, namely construction workers.” Dajun quickly settled in Lengquan vilage, an area outside Beijing’s fifth ring with a large migrant population. Together with others he jointly rented a small yard consisting of five rooms, counting the toilet. At the time, Dajun lived in a windowless ten square meter room just big enough to fit a bed and a coal briquette stove for heating during the winter. His rent was 200 yuan. Some in the non-profit would say to him: It must be hard to live and eat like to the people you help. But Li Dajun would say: “No! After dinner you drop in on people, chat. I think it’s great!” He always believed that as a social worker he should spend time with workers in order to stay grounded and stay sensitive to society.

Through hard work, Dajun and the group of student volunteers providing service for construction workers slowly started growing bigger. In 2016, Dajun introduced the services the organization was providing at a sharing meeting open to the public: rebuilding workers’ recognition of the value of their labor and dignity through visiting construction sites and recording workers’ stories, breaking the isolation of workers by expanding their social network through organzsing construction site reading and interest groups, educating workers through newspapers and construction site reading rooms, spreading information about labor law and policies, promoting awareness and developing capacities through case counseling, establishing workers mutual help networks through practical training, promoting the establishment of construction workers’ trade unions and cultivating the collective strength of workers, and linking resources to form joint forces for policy advocacy and outreach.

During his years of research on and providing service to construction workers, Dajun gradually realized that without changing the capital dominated production methods and surpassing their profit driven logic, there is no way to effectively solve the basic labor security problems of workers. Therefore, in 2011, Dajun and other volunteers tried to organize a communist construction group at the construction site: there was no contractor, everyone would take up projects together, and everyone participated in the distribution of profits. Later, they also tried to organize a furnishing cooperative. These projects were successful on a small scale. Although resources have limited these projects’ growth, these repeated attempts by Dajun and friends are extremely valuable in today’s China.

In addition to practice, Dajun has also made important contributions in thinking and writing. As an advocate of public welfare who has long been deeply involved in helping construction workers, he was often interviewed by mainstream media on construction workers’ issues and often commented on various issues of labor relations in the construction industry. In addition, he also kept a blog on Caixin.com, where he always maintained the bottom-up perspective of workers. He talked about not only labor contracts, work-related injuries and occupational diseases of construction workers, but also reflected on the excessive marketization of China’s current development and the single minded focus on profits. After reading his blog, I started admiring him even more: in all the indifference of our money obsessed era, he, without a second thought, fully dedicated more than ten years of his life to thought and action to make this society better.

Good to workers and “stern” with himself

Anyone who knows Dajun can tell you that he always cared about workers. The most prominent example of this is his 10 year effort to help the Hunan’s pneumoconiosis workers. In July 2009, Hunenese pneumatic drill workers suffering from pneumoconiosis went to Shenzhen to claim their rights. By chance, Dajun was able to contact these workers in his personal capacity. At that time, he and several representatives of pneumoconiosis affected workers right’s defence effort met for the first time in a private room on the third floor of a hot pot restaurant. He would explain that [when he chose the place where to eat] he was sure that he thought things over very thoroughly: Hunanese people like spicy food and this is what they were going to have. It turned out, however, that as Dajun was waiting for them he could hear footsteps coming from the stairway that were becoming slower and heavier as they got closer, it sounded as if the people climbing the stairs were carrying heavy loads. As soon as he opened the door a group of people, inpatient to get in, rushed through the door drenched in sweat and quickly sat down gasping for air. “There was no need for any explanation. Their hungry breathing was enough to tell me that their lungs were no longer functioning properly. After climbing just three floors, their breathing could only be described as ‘desperate’. This was the first time I saw silicosis affected workers. I knew immediately that there was no way I could follow their actions as a mere observer.”

Later, Dajun quickly mobilized university student volunteers and their teachers to do research, accompany the workers to sit-ins, write letters to the mayor, contact the media and cultural celebrities, do everything they could think of and focus all the strength they could gather to deal with this issue. During the May 1st holiday this year, Dajun bought a hard seat train ticket and took a 20 hour train ride to Hunan ‘s pneumoconiosis villages to visit the seriously ill workers and give them donations from supporters, gather data on orphaned children of pneumoconiosis victims which he planned to take back to Beijing to continue updating supporters and raise more money for the orphans of pneumoconiosis victims… But now, all this has been interrupted!

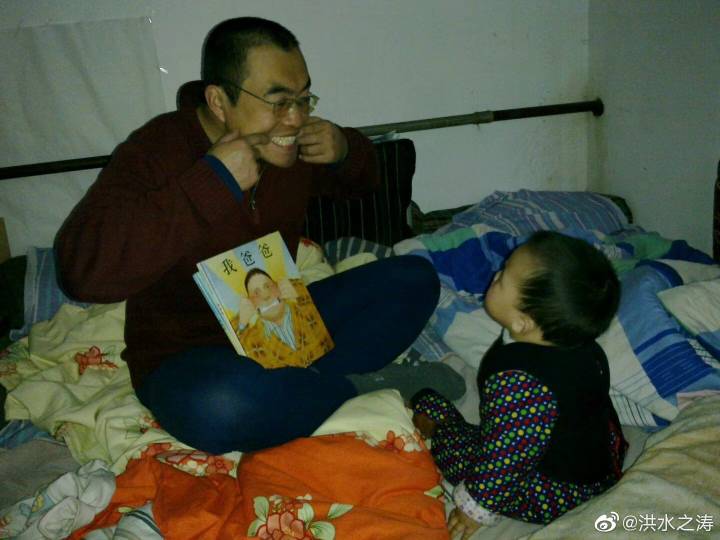

Dajun’s life was extremely frugal, he was almost “stern” with himself. In Lengquan, he and his family lived in very rudimentary conditions. For many years, they relied on burning coal for heating. The electric water heaters were only installed in the past two years. Dajun mostly ate the cheapest food bought from street stalls, and no matter if he ate at home or outside he never wasted one bite. When he went on a trip, he would only buy [the cheapest] hard seat train tickets in order to save money. I often told him, you are too hard on yourself! But Dajun did not agree, and told me that his living conditions were already very good. Workers from Lengquan village can’t afford to drink milk even once a week, and they have no heating equipment at home, he would say.

This outstanding advocate of public welfare who lived as he preached was taken away on May 8th, by the Beijing police. His residence and office in Lengquan were searched. The police officers who conducted the search reportedly also interrogated other staff members to establish whether there were any foreigners, Taiwanese or Hong Kong people who visited, where the community’s funding came from, and whether there was any subversive discourse. Now, Dajun has been missing for more than a week with no news of him. Lengquan Hope Community’s operations have always been transparent and open. If these problems existed at Hope Community, why would they choose Hope Community as the China Youth Development Foundation model project? We have all witnessed Dajun’s ten years of words and deeds, which part of that was “subverting the state”?

The bad news about Dajun came out of the blue. I still baffles me. I can only use the bit of reason I have left to tell everyone what kind of a person Dajun is and what he strives for. If you are like me, and believe that Dajun is not guilty, and hope that he will be able to go back to serving workers as soon as possible, please forward this story and let more people know the truth!

Ke Chengbing

Ke Chengbing